Selenium plays an important role in optimal immune and endocrine system function. The role that selenium plays with respect to thyroid function is complex [Chmura 2022]:

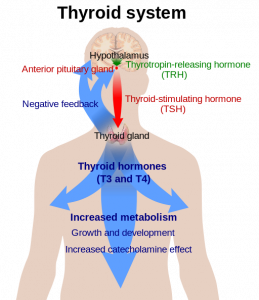

Good thyroid system function promotes improved metabolism, better growth and development, and increased effect of catecholamines. Note: Catecholamines are hormones released in response to emotional or physical stress. (Attribution: Mikael Häggström, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.) The thyroid gland is the organ with the greatest amount of selenium per gram of tissue.

- An adequate supply of selenium is necessary for synthesizing the enzymes – the iodothyronine deiodinases – that are involved in the metabolism of thyroid hormones.

- Selenium supplementation may give beneficial effects to patients with autoimmune diseases of the thyroid gland.

- There is a significant correlation between selenium deficiency and thyroid gland dysfunction. Selenium deficiency is defined as serum or plasma selenium levels below 70 mcg/L. Optimal serum/plasma selenium levels are approximately 125 mcg/L [Winter 2020].

Selenium Deficiency and Thyroid Dysfunction

A 2022 review highlights the following relationships between selenium deficiency and thyroid gland dysfunction [Chmura 2022]:

- Selenium levels are often low in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis.

- Selenium supplementation may lower TPO-Ab and Tg-Ab antibody levels in patients with Hashimoto’s disease (the most common form of hypothyroidism).

Note: Thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO-Ab) act to prevent thyroid peroxidase from catalyzing the formation of T4 thyroid hormone. Elevated levels of TPO-Ab antibodies are an indication of an autoimmune disease such as Hashimoto’s disease or Graves’ disease.

Note: Thyroglobulin antibodies (Tg-Ab) hinder the functioning of the protein thyroglobulin in the synthesis of triiodothyronine and thyroxine hormones. Elevated levels of Tg-Ab are an indication of an autoimmune thyroid disorder.

- Administration of supplemental selenium to patients with Graves’ orbitopathy has resulted in delayed progression of the orbitopathy and in less disease severity. (Some 50% of Graves’ disease patients suffer from orbitopathy – swelling of the tissue in the area around the eyes, causing a bulging of the eyes.)

- Selenium supplementation may also increase the effectiveness of anti-thyroid drugs in patients with Graves’ disease (the most common form of hyperthyroidism).

- There is an association between selenium deficiency and the development of goiter and thyroid nodules.

- To date, the scientific evidence for selenium supplementation in pregnant women with autoimmune thyroiditis is inconsistent.

Intakes of Selenium and good health

The human body does not synthesize selenium. The intake of selenium depends on the diet, which is influenced by the selenium content of the soil and the food in a particular region. The availability of selenium varies considerably from region to region [Haug 2007; Stoffaneller & Morse 2015].

Selenium intake data have shown that 500 million to one billion people worldwide can be regarded as selenium deficient, using the reference value of 70 mcg of selenium per liter in serum or plasma [Haug 2007].

- Achieving an optimal expression of selenoprotein P, the primary selenoprotein that transports selenium in the blood, requires an estimated daily intake of 100–150 mcg/day of selenium [Alehagen 2022].

- Achieving an optimal expression of many selenoproteins requires about 120 mcg/L when measured in the red blood cells [Alehagen 2022].

- Sub-optimal selenium levels (below 100 mcg/L) are associated with lower exercise capacity, lower quality of life, and worse disease prognosis [Al-Mubarak 2021].

How Selenium Helps Thyroid Gland Function

Selenium plays an important role in the functioning of the thyroid gland in two ways [Chmura 2022]:

- Selenium is an essential component of the antioxidant family of glutathione peroxidase selenoenzymes, which provide protection against oxidative stress in the thyroid.

- Selenium is an essential component of the iodothyronine deiodinase selenoenzymes, which are needed for optimal thyroid hormone T3-to-T4 ratios and for optimal TSH levels.

The thyroid gland is preferentially supplied with selenium. The immune system is not accorded the same high priority for selenium supply. Thus, low selenium intakes are less likely to affect thyroid cells than immune system cells.

Prof. Lutz Schomburg, Berlin explains: In selenium deficiency, the interaction between the immune system lymphocytes and the thyroid gland cells can become disturbed and sub-optimal. This is especially likely whenever the thyroid gland is challenged by infection, trauma, shock, pregnancy, iodine deficiency, or toxins [Schomburg 2019].

Conclusion

Habitual low selenium intakes increase the risk of thyroid disease, both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, particularly in males [Schomburg 2019].

Several selenoproteins – including Selenoprotein P, Selenoprotein S, Selenoprotein K, several glutathione peroxidases, two iodothyronine deiodinases, and two thioredoxin reductases are vital to optimal thyroid gland functioning [Winther 2020].

In patients diagnosed with chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, selenium supplementation reduces circulating levels of thyroid autoantibodies, as compared to placebo supplementation [Winther 2020; Chmura 2022].

Certain patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, or Graves’ orbitopathy respond positively to selenium supplementation [Schomburg 2019].

Selenium supplementation may be important for individuals with known selenium deficiency (plasma/serum selenium concentrations below 70 mcg/L) and for individuals with marginal selenium deficiency (plasma/serum selenium concentrations between 70 and 85 mcg/L). The optimal plasma/serum selenium concentrations seems to be around 125 mcg/L [Winther 2020].

Research studies have not shown any toxicity associated with selenium supplementation dosages of 50-200 mcg/day [Schomburg 2019].

Sources

Al-Mubarak AA, van der Meer P, Bomer N. Selenium, Selenoproteins, and Heart Failure: Current Knowledge and Future Perspective. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2021 Jun;18(3):122-131.

Alehagen U, Johansson P, Svensson E, Aaseth J, Alexander J. Improved cardiovascular health by supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10: applying structural equation modelling (SEM) to clinical outcomes and biomarkers to explore underlying mechanisms in a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled intervention project in Sweden. Eur J Nutr. 2022 Sep;61(6):3135-3148.

Chmura A, Baciur P, Skowrońska K, Białas F, Pondel K. Influence of selenium deficiency on the development of thyroid disorders – a literature review. Journal of Education, Health and Sport. 2022;12(9):525-531.

Haug A, Graham RD, Christophersen OA, Lyons GH. How to use the world’s scarce selenium resources efficiently to increase the selenium concentration in food. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2007 Dec;19(4):209-228.

Schomburg L. The other view: the trace element selenium as a micronutrient in thyroid disease, diabetes, and beyond. Hormones (Athens). 2020 Mar;19(1):15-24.

Stoffaneller R, Morse NL. A review of dietary selenium intake and selenium status in Europe and the Middle East. Nutrients. 2015 Feb 27;7(3):1494-537.

Winther KH, Rayman MP, Bonnema SJ, Hegedüs L. Selenium in thyroid disorders – essential knowledge for clinicians. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 Mar;16(3):165-176.

The information presented in this review article is not intended as medical advice and should not be used as such.

The information presented in this review article is not intended as medical advice and should not be used as such.

30 October 2022